Localisation Techniques

The Forward and Inverse Problem

In an ideal world the problem of localisation is barely a problem at all. Time delays can be calculated, bearings crossed and a location calculated. A rigorous and concise mathematical derivation of this is found in Magnus Wahlberg et al. However biological studies are not conducted in vacuum, seawater is not a still homogeneous medium and cetaceans are not perfectly spherical acoustic sources. As discussed in the localisation overview section error is inherent in every part of a hydrophone monitoring system, from the position of the hydrophone, to the digitisation and cross correlation of a detected porpoise click. Therefore instead of having cones, which perfectly intersect at the exact location of the cetacean, in reality there exists a set of cones, which roughly intersect each other in a certain area or perhaps do not intersect at all. This creates an obvious problem. If there is no exact intersection point, where is the cetacean?

The process of calculating and crossing bearings to find an intersection point is generally named the inverse problem. The inverse problem refers to a situation were for a given set of observations (time delays) the initial parameters (location of the cetacean) are directly calculated. The advantage of this system is that it is very computational efficient however, it is also particularly vulnerable to errors. Although cones may roughly intersect around a likely cetacean position, quantification of the error in location is difficult and therefore the inverse problem does not provide an intuitive or satisfactory solution to real world localisation. Instead for many localisation algorithms one must look at the forward problem: calculating the observables from a given set of parameters. In terms of localisation this refers to selecting a point in space, calculated the theoretical time delays, or bearing angles from hydrophone clusters, if the cetacean was vocalising at this point in space and then comparing the theoretical delays to the actual observed time delays or bearings. The more similar the theoretical and observed time delays the closer the point in space is to the actual position of the source position. By sampling many different locations the localisation algorithm can select that location which best fits the observed data. While this may sound highly inefficient, algorithms exist which can efficiently test multiple locations and converge on a solution sufficiently fast for real time operation on most modern computers.

Least Squares

Least squares methods are generally solving the inverse problem. Examples are found in hyperbolic localisation methods within the Group 3D localiser, where the least squares crossing point is calculated for multiple hyperbolae, each derived from a time difference of arrival on a pair of hydrophones. Another example is one of the target motion algorithms, which takes a set of bearings to an animal from multiple points along a track-line and finds the least squares solution to the crossing point of those bearings.

Simplex, or Nelder-Mead

Simplex, or Nelder-Mead methods are a commonly used way of solving the forward problem, i.e. guess an animal location and calculate theoretical values for the observed data (bearings, time delays, etc.), test the observed data against those values, move the animal a bit and see if updated theoretical values better fit the data, keep updating until the fit is as good as it can get. While this sounds computationally intensive, the Nelder-Mead method varies the step sizes as it tests different locations and is incredibly efficient at finding the optimal solution. Within PAMGuard these methods are used to cross bearings within the target motion algorithm, to cross bearings in the Group 3D localiser and also to estimate 2 and 3D locations direct from time delays using alternative algorithms within the Group 3D localiser

MCMC

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) is a Bayesian statistical technique that has been applied to a large variety of problems, from estimating the solutions of complex integrals, to searching for exo-planets. The basic premise is to calculate a series of estimates which gradually increase in accuracy until a satisfactory solution is reached. The estimates form a chain of results which then bounces around the likely solution creating a probability distribution of results.

In terms of acoustic localisation MCMC is particularly useful due to its ability to easily incorporate experimental unknowns and then provide dynamic visualisations of the resulting errors. Utilising both real and simulated data this allows rigorous analysis of the effectiveness of a hydrophone array and easy quantification of the error for each individual localisation.

For acoustic localisation, parameter space generally refers to the Cartesian (or other) co- ordinates (x,y,z) but could also include other variables which would alter the theoretical time delays. These can include sound speed, salinity, hydrophone positions, and/or the angle of a vertical array.

The process begins with a random point in parameter space. From this initial point in space a random jump is executed. A jump involves changing each parameter value by a limited but random value. For example if the only parameters changing were the x.y,z co-ordinates then each jump would simply be a random jump through 3D space. Once a jump is executed a measurement of whether the new parameters are closer to the solution is undertaken. This is a chi squared value. The chi squared value compares the theoretical time delays calculated from the new jump location to the observed time delays. The lower the chi squared value the greater the similarity is between the theoretical and observed values. After jumping and calculating the new chi squared value the Markov chain then follows a series of three sequential rules. These are based on the difference between the previous and new chi squared values;

1. If the new chi squared value is less than the previous chi squared value then the jump is accepted.

2. If the new chi squared value is greater than the previous chi squared value then the jump is only accepted with a probability of;

were delta chi squared is the difference in chi squared between the previous and new jump point.

3. If neither of the two above criteria is achieved the jump is not accepted and another random jump is executed from the previous point.

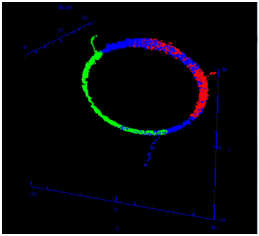

The result is a sequence or chain of jumps, which converge to form a cloud of points around the likely position of the acoustic source. The density of this cloud then represents the probability distribution of the acoustic source location in space. Figure 1. shows three MCMC chains converging to form a circular probability distribution. Here the acoustic source could be anywhere on a circle of possible locations, a common result when using linear arrays.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Although this process requires large amounts of computational power the rapid progress of multi-core computing means it is possible to have multiple chains without a large increase in computational time.

_References

Magnus Wahlberg, Bertel M?hl and Peter Teglberg. Estimating source position accuracy of a large-aperture hydrophone array for biacoustics. J. Acoust Soc. Am. 109. 397-405

Stacy Lynn Deruiter. Echolocation-based foraging by harbour porpoises and sperm whales including effects of noise and acoustic propagation. PhD thesis, (2008).

Line A. Kyhn, J. Tougard, F. Jensen, M. Wahlberg, G. Stone, A. Yoshinaga, K. Beedholm and P.T Madsen. Feeding at a high pitch. Source parameters of narrow band, high frequency clicks from echolocating off-shore Hourglass dolphins and coastal Hector’s dolphins. J. Acoust. Soc. Am .125, 1783-1791 (2009)

Mathew J. Holman, Joshua N. Winn, David W. Latham, Francis T. O’Donovan, DavidCharbonneau, Gaspar A. Bakos, Gilbert A. Esquerdo, Carl Hergenrother, Mark E. Everett and Andras Pal. The Transit light curve project. I. four consecutive transits of exoplanet XO-1b. The Astrophysical Journal. 652: 1715-1723 (2006)_